Tie-Downs

Use of Restraints, PART 1

December 2002 • Volume 27 • Number 12

Chances are one of the silly parts of your EMT training was learning to say, "Scene safety, BSI," whenever you walked into a simulation or a testing station. What, did they think you were a parrot? That was a bad joke, and it wasn't very funny.

Scene safety is the most important part of every call you'll ever run, and if you're like most EMTs you didn't really learn much about it before you hit the street – especially when it comes to using restraints. Tying people down is dangerous work, and underestimating them is even more dangerous.

Sometimes you're called to a psychiatric facility where a schizophrenic patient has cut himself or maybe OD'd, and your job is to take him to the ED for evaluation. Other times, you might respond to a private residence in the middle of the night, all by your lonesome, and the patient's complaint seems kinda vague. You might leave a scene where you were surrounded by more than one crew, and find that when you're in the back of the ambulance on your way to the hospital, the patient's behavior changes. Who teaches you how to deal with this stuff?

If you've never had a thorough class on how to restrain someone, you need – and deserve – one. Do yourself and your whole agency a favor: Ask for one today. And if it hasn't happened a month from now, insist on it – and insist on it again – until you become the EMT from hell. (EMTs from hell get things changed.)

It's your job to be nice to people, Life-Saver. But don't be a ditz. Remember, you're valuable. You're irreplaceable. Someday you may decide to give up your life for someone else. But don't throw it away, not ever, not for anyone.

Next month, we'll demonstrate a safe way to tie someone down. Meanwhile, consider the following general "people principles" that can keep you out of trouble most of the time.

- When you leave home for your shift, wake up! Switch your mentation to a mild alert status and keep it that way. Orient yourself to coming back safely.

- Remember, people all around you don't think the way you do. If they're impaired, their behaviors may not be rational in your terms. If they're predatory, chances are they don't respect the things you respect or care about the things you care about. And most importantly, they look like everybody else.

- When somebody calls 9-1-1, either they can describe their emergency (SOB, chest pain, stabbing, etc.) or they are clearly impaired. When you respond, you deserve to know what you're responding for. Insist on that much from your dispatchers, or ask for the PD to respond and evaluate the situation prior to your arrival.

- Take a critical look at every scene before you go waltzing in like a dumb***. Things are supposed to make sense. If they don't, they're dangerous until proven otherwise.

- Don't run, no matter what you see and no matter how frantic people seem to be when you arrive. Walking gives you more time to analyze what's going on and keeps your catecholamines under control so you can think and communicate more clearly. (It also prevents the jitters.)

- Learn to respect the fact that when you enter someone's home, you're on their turf. They know everything about it, and you know only what your senses tell you. That puts you at a distinct disadvantage.

- When you ask somebody a question in black-and-white, Anglo-Saxon English and they respond with the story of the three bears, two things should enter your mind right away: One, maybe they're impaired. And two, maybe they're hiding something.

- Most violent situations in EMS result from our own disrespect. Remember your role as a caregiver, and treat patients and their families with dignity and respect – even if they're cranky (on what may be the worst day of their lives).

- If you find a weapon on somebody, pay attention to what type it is and make the appropriate inference. (Is it one you would use to hunt elk or hold up banks?) Involve the PD, right away. Then look for another weapon. In fact, it may be a good idea to strip these patients naked – respectfully and protecting their modesty, of course.

- If all else fails, read next month's JEMS to find out what this fool author says about tying people down.

Straight Shot

Use of Restraints, PART 2

January 2003 • Volume 28 • Number 1

As we said last month, tying people down against their will isn't a game – it's dangerous work, and underestimating it is even more dangerous.

There's nothing worse than getting yourself knee-deep in restraints with too little help and forethought, then having some little old lady with blue hair open up a whole case of whup-ass on you. You and your partner need a plan and three strong people to help you, period. (Don't make excuses like "we work nights" or "we're rural" or somebody will get hurt.) You need to share your plan with your three helpers in advance, and then practice with real people and real equipment.

Photo by Thom Dick |

|

First, get your equipment, especially the ambulance cot, as close to the patient as you can. If you can, surround the patient someplace where there's room to work – preferably not next to a cabinet full of china and crystal. Try to use a predesignated audible signal, like "We seem to have no choice ..." to prompt everyone to act at once. Then, proceed promptly as follows:

With the cot close by, all five providers should surround the patient (see Photo 1). |

The tallest person should move behind the patient and, grasping them by the hair, pull their head far enough back to expose the front of their neck. (If they don't have hair, grab an ear.)

| As soon as that happens, the person at the head should quickly use the crook of their opposite arm to cradle the front of the patient's neck. This enables you to do two things: 1) prevent the patient from biting you or anyone else and 2) see and direct the rest of the team's activities. If you're at the head, it's your job to talk to the patient in a calm voice, reassuring them that you mean them no harm.

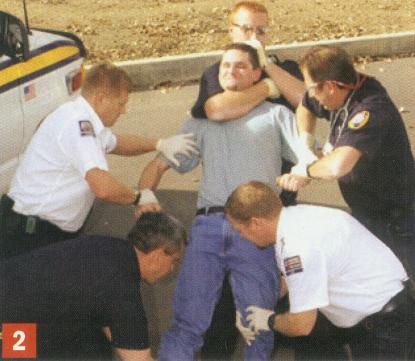

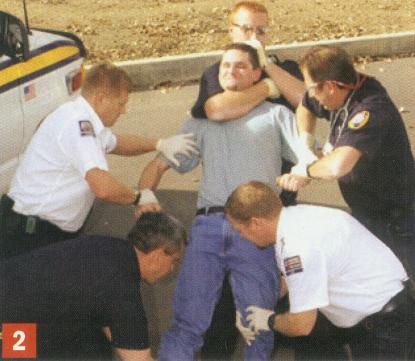

It's essential that as soon as you grab the patient's head, everyone else on the team grab different distal extremities with both hands, and hold on tight (see Photo 2). |

|

Photo by Thom Dick |

Photo by Thom Dick |

|

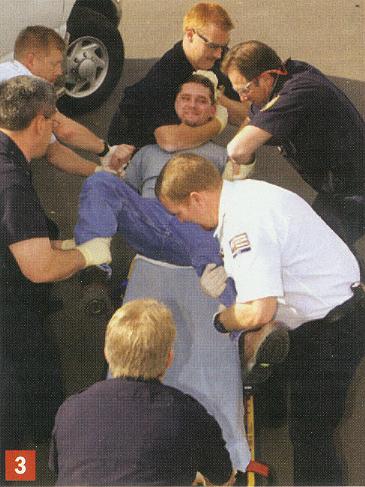

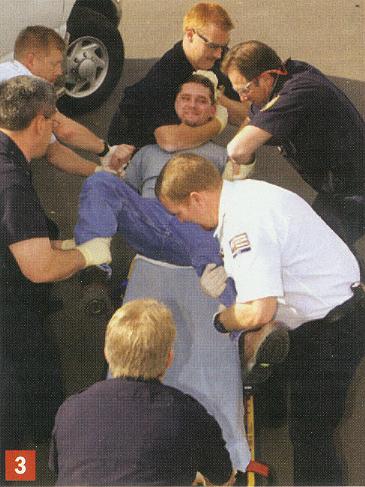

The patient will struggle forcefully enough to lift his own weight off the ground. If a bystander is available, direct them to roll the cot underneath the patient (see Photo 3).

Otherwise, you'll all need to move toward the cot and place the patient on it in a supine position. |

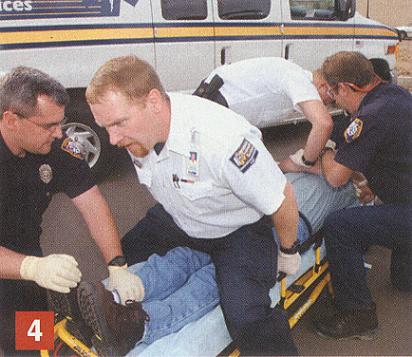

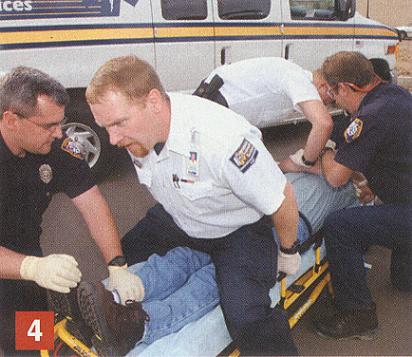

| As soon as the patient is on the cot, a team member at the foot end needs to straddle the patient's knees and sit on them, facing the patient's feet (see Photo 4).

That team member can control the pressure they exert on the patient's knees by holding onto the upper frame of the cot. In doing so, they free up whoever is holding the other ankle. |

|

Photo by Thom Dick |

Photo by Thom Dick |

|

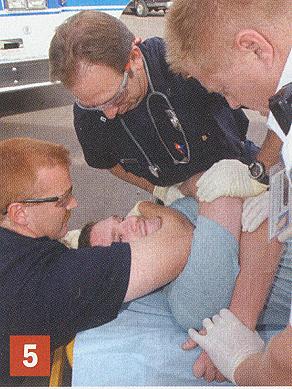

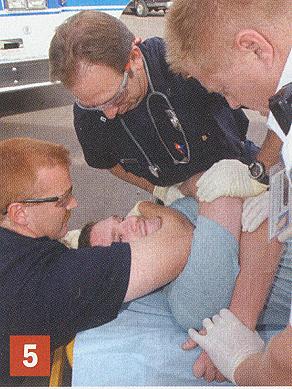

As that team member frees themself, the two people holding the patient's arms should criss-cross the patient's arms across their chest, exchanging the arm they're holding in the process. This restrains the patient with their own upper extremities (see Photo 5).

Remember, you want to restrain the patient with the least amount of force necessary.

The "free" caregiver, who started out holding onto an ankle, should be applying restraints – first to the wrists (because the caregiver on the knees is in the position of greatest strength) and then to the ankles. This should be done one extremity at a time. |

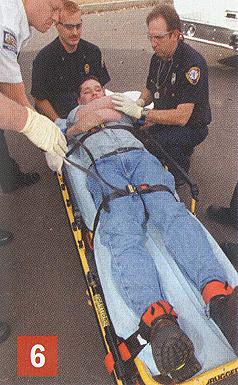

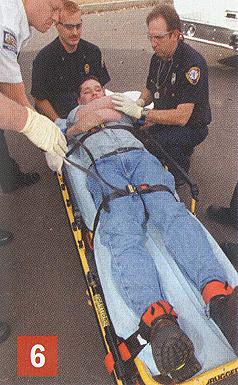

| Once you have firmly secured all four distal extremities, it's absolutely essential to strap the patient's knees firmly to the cot's upper frame (see Photo 6).

If the patient can flex the knees, they can pull their head and shoulders out from beneath their arms, flip over and position themselves on their hands and knees – completely destabilizing the cot. It's just as essential to strap the wrists firmly to the cot's upper frame, below the part that can be tilted to raise the head and shoulders.

Don't let go of the head and neck until all four extremities and the knees are firmly fastened. From that point on, you'll be able to tighten both arms simultaneously by simply raising the head end of the cot into a mild Fowler's position. Pressure can then be relaxed or intensified as necessary. Let go of the hair last, after you have quickly removed your forearm from biting distance. |

|

Photo by Thom Dick |

The following are critical principles you should always remember in any restraint procedure:

- Human bites can be terrible injuries. They almost always become infected and can be difficult to repair.

- Do not choke the patient! Keep the trachea aligned with the crook of your arm, and apply only enough force to keep the head under control.

- Take care not to hyperextend the patient's knees by applying excessive force, especially while sitting on them.

- No matter what the patient says or does, remember they may believe they're fighting for their life – especially when under the influence.

- Keep all team members calm and quiet, and avoid shouting. No matter what you do, avoid insulting the patient under any circumstances.

- Remember, the patient who gets restrained stays restrained until they arrive at the hospital and/or can be chemically sedated.

- Keep the cot in its lowest position at all times during a restraint procedure. That stabilizes the cot and lowers the team's collective center of mass – all of which allows the team to use their weight, requiring the least amount of exertion on their part.

- Pay close attention to the patient's respiratory, circulatory and skin signs. We restrain people to immobilize them for treatment and safety, not to punish them, hurt them or humiliate them.

- A patient who continues to struggle after you restrain them should be chemically restrained as soon as possible. Persistent violent struggling can induce systemic acidosis, electrolyte imbalance, cardiac dysrhythmias and/or death.

- If you suspect that you'll be unable to safely restrain someone with five team members, don't hesitate or be embarrassed to call in law enforcement to do the restraining for you. Then ask them to accompany you to the hospital.

- Remember, the patient who is found in legal custody stays in legal custody.

- Finally, search for weapons. If you find one, look for others, and pay attention to what kinds of weapons they are. (Are they for hunting elk or hurting people?) If you do find weapons, always involve law enforcement.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the following, without whose help these illustrations would not have been possible: Dennis Baker, Jerry Luft, Robert Putfark, Lt. Sean Schwartzkopf, Mark Seidel, the Arvada Fire Department and Pridemark Paramedic Services. All Photos by Jeff Forster

Publishing and Reprint Information

- Thom Dick has been an EMT and a paramedic for 23 years and is the quality care coordinator for Pridemark Paramedic Services, Arvada, Colo.

- Contact him via

email at: Boxcar414@aol.com.

email at: Boxcar414@aol.com.

- For JEMS reprints or permissions visit www.jems.com/jems/back.html or contact the Copyright Clearance Center at 978/750-8400 or visit www.copyright.com.

Go To: CHAS' REVIEW of this 2-Part Column

This review was written and posted on January 23, 2003.

USE YOUR BACK BUTTON

To Return To Wherever You Came From

OR:

Return to the Restraint Asphyxia LIBRARY

Return to the Restraint Asphyxia Newz Directory

Return to CHAS' HOME PAGE

Email Charly at: c-d-miller@neb.rr.com

Email Charly at: c-d-miller@neb.rr.com

Those are hyphens/dashes between the "c" and "d" and "miller"

email at: Boxcar414@aol.com.

email at: Boxcar414@aol.com.

Email Charly at: c-d-miller@neb.rr.com

Email Charly at: c-d-miller@neb.rr.com